Since the human body loses about 50 million skin cells each day, they are constantly in a state of regeneration. The lifespan of skin cells is approximately four weeks.

From Sciencing – Though it is often said that your body changes every seven years, this not completely accurate. While the human body is constantly in a state of regeneration, each type of cell has its own schedule. The human cell turnover rate differs based on location and function.

For instance, the stomach lining is constantly eroded by digestive acid and needs to be replaced every few days. On the other hand, it takes years for bones to be refreshed and in some body parts, such as the brain, many cells remain from the time of birth.

There are about 37 trillion cells in the adult human body, and almost 2 trillion of these divide each day. Most of these cells are somatic (non-reproductive) cells and divide through a process called mitosis, creating new cells identical to the parent cells.

-The Body’s Largest Organ

Though it is only a few millimeters thick at its thickest point, the skin is the body’s largest organ and makes up about one-seventh of one’s body weight. On average, it weighs between 7.5 and 22 pounds with a surface area of 1.5 to 2 square meters.

Since it is regularly exposed, it requires frequent cell regeneration. When you get a cut or scrape, skin cells divide and multiply, replacing the skin you have lost. Even without injury, skin cells routinely die and fall off. You lose 30,000 to 40,000 dead skin cells each minute, which is about 50 million cells every day.

Skin provides vital protection to all other organs. It also protects the body as a whole from harmful things such as excessive moisture, extreme temperatures, germs and toxins. Other functions include helping to regulate internal temperature and alerting the brain to various sensations such as itching and pain, sometimes preventing serious injury.

-Three Levels of Skin

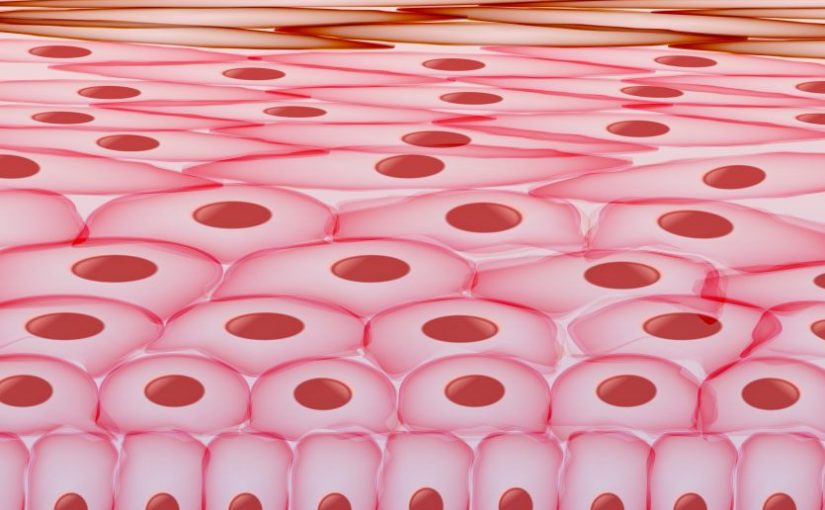

The epidermis, or outer layer, is the part you can see. It varies in thickness, depending on location. While it may be up to 4 millimeters thick on your feet and hands, it is often only 0.3 millimeters thick on places such as your eyelids, elbows and the back of your knees.

It is made up of dead skin cells that are firmly packed together and constantly shedding. The epidermis contains other types of cells that perform special functions. Melanocytes make and store melanin, which protects against the sun’s UV rays. When skin is exposed to the sun, they produce more of this pigment, making your skin darker. Lymphocytes and Langerhans cells fight germs by “grabbing” them and taking them to the closest lymph node. Merkel cells are nerve cells that help sense pressure.

The dermis, or middle layer, is made up of a network of elastic collagen fibers that make the skin both strong and stretchy. The dermis is also home to a network of nerves and capillaries that help your body cool down. In some areas, the dermis extends into connective tissue, connecting the two. Of the three layers, the dermis has the most sensory cells and sweat glands.

The hypodermis, or deepest layer (also called subcutaneous or subcutis), is made up mostly of fat and connective tissue. Cavities in this layer are filled with storage tissue (fat and water) that acts as a shock absorber to bones and joints and also serves as insulation. This is where vitamin D is produced when skin is exposed to sunlight. Blood and lymph vessels, nerves, sweat, oil and scent glands and hair roots are also found at this level.

-Lifespan of Skin Cells

While we sometimes notice the shedding of old skin, most of the time these cells are too tiny to notice, and we are unaware we are leaving these traces of our DNA behind.

These departing cells are constantly being created in the lower layers of the epidermis before moving to the surface where they harden and fall off. This process of growing, moving and shedding takes about four weeks.

-Skin Regeneration After Wounds

The process is more obvious when skin is lost due to a cut or other injury. While regrowth is similar to routine human cell regeneration, it has some extra steps.

First, collagen spreads to the wound area to create a framework that will support the new skin. Then, a network of blood vessels migrates to the area, followed by skin and nerve cells. Finally, the hair pigment, oil and sweat glands may regenerate.

If the wound is too deep, it may be missing some of these components and may not grow back properly; infection can slow the process. Even under the best circumstances, the new tissue produced often varies slightly from the original and results in a scar.

How Does Skin Regenerate?

Bodies are often compared to machines, but unlike machines, your body and its organs can regenerate in response to injury, poisoning or other trauma. The degree to which this occurs varies from organ to organ; for example, liver tissue and skin possess remarkable regenerative abilities. Scientists continue to learn more about how, for example, keratinocytes in the epidermal skin layer proliferate in response to local damage. Your skin’s regenerative capacity is critical given its role in serving as a protective barrier between your internal organs and an often hostile outside world.

-Skin Basics

Your skin consists of three layers. The outermost of these is the epidermis, which consists chiefly of cells called keratinocytes. These cells form several layers of their own, and as keratinocytes grow and mature, they migrate from the bottom of the epidermis to the surface of the skin. The next layer, the dermis, lies beneath the epidermis. Thanks to its density of collagen and elastin fibers, the dermis is what gives your skin its real substance. Your skin’s nerves and blood vessels course through the dermis. Finally, the even deeper subcutis houses fat that serves as a fuel source as well as a cushion in the event of falls and other trauma. Each of these layers is capable of regeneration, but the process differs from layer to layer.

-Initial Response

When something happens to disrupt the integrity of your skin to the extent that it has to regenerate, your body’s immediate response is inflammation. White-blood cells leak out of local blood vessels into the wound, which could be a scrape, cut or burn. Next, various immune cells – including T-cells, Langerhans cells and mast cells – release chemicals called chemokines and cytokines. These substances draw other cells, such as macrophages, to the area. The result of this cascade is the release of nitric oxide and other substances that drive the initial stages of angiogenesis, which is the creation of new blood vessels to replace any that were damaged in the precipitating incident.

-Regeneration of the Epidermis

Repair of damage to the epidermis starts with the deepest part of the epidermis — the stratum basale. The first stage of regeneration involves proliferation of the cells of the stratum basale itself. Once this is finished, all that’s required is for the cells of this layer to continue to divide and migrate upward to fill whatever space remains above. In the case or more superficial cuts, bleeding is absent and the process merely begins with the proliferation of cells of the intact stratum basale.

-Regeneration of the Dermis

Injuries that penetrate through the epidermis all the way to the dermis set in motion a process distinct from epidermal regeneration. The most important cells in this process are called fibroblasts. These are highly mobile cells, so they can move from the healthy portion of the dermis at the edges of the wound into its interior. Here, they secrete matrix fibers – chiefly collagen and elastin – that form the substance of the regenerating dermis. Meanwhile, macrophages act as scavengers, crawling about and engulfing scab material and anything else that constitutes waste.

Further Reading – Supporting Your Skin Throughout Its Lifespan

Lifespan of Skin Cells: Started at the Bottom

The life story of a skin cell is one of triumph. If it were a movie, it would be about a heroic climb from the depths all the way to the highest heights. But this isn’t an underdog story. The lifespan of your skin cells is the best way for your skin to do its job.

A skin cell’s life starts from humble beginnings at the bottom of the epidermis—your topmost of your skin’s three main layers. All your skin cells are born at the junction of the epidermis and the dermis. They all start out full of proteins—keratin and collagen—and shaped like a chubby square.

It’s an unassuming start to life for the cells that protect your body from the outside world. But things definitely get better—and harder.

-The Climb

Over the next month, these fat, square cells, born at the bottom, will ascend to great heights within the epidermis. As new cells are born, they facilitate the climb, pushing existing skin cells towards the top layers. That flattens out your skin cells as they’re pushed upward.

This is a tough time in the lifespan of skin cells. The arduous journey hardens them and prepares skin cells to do the tough work of shielding the body from the outside world.

No skin cell survives the climb. Because that’s what they’re supposed to do—die.

-No Rest for the Dead

All the skin you’re looking at right now is dead. You have to dig down about 20 layers from the outside of your skin to find a living skin cell.

They aren’t alive, but that doesn’t mean your skin cells are done working for your health. These flattened, hardened cells create layer upon layer of protection.

The top layers of dead skin cells act like the shingles on a roof. They overlap to form a water-tight barrier. That’s how the zombie skin cells keep out the unwanted parts of your environment.

Eventually, all skin cells are pushed out by the new cells making the climb. The never-ending procession of cells from below helps dead cells reach the very top layer. At the pinnacle, they flake off.

-The End: Into Dust

Your noble, triumphant skin cells—the shields that protect you day and night—meet a fairly gross fate. They literally turn into dust.

A lot of the dust in your house is actually dead skin. In fact, you produce about eight pounds (3.6 kilograms) of skin-cell dust per year. You’re surrounded by the discarded parts of your skin.

So, next time you’re wiping off the counter or dusting your dresser, say thanks. And pay your respects to the tough, triumphant lives lived by your former skin cells.