Modified slightly and adapted from chapter 03 of Eat for Life-The Food and Nutrition Board’s Guide to Reducing Your Risk of Chronic Disease (1992)

It is commonly thought that the U.S. diet has become healthier since the last century. We live longer, grow taller, and enjoy better health than our ancestors. Diet has had some part in the health benefits we have realized over the years. Deficiency diseases are rarely seen in the United States today. But we now live longer primarily because of improved sanitation, antibiotics, and vaccinations—infectious diseases are no longer the major killers they once were. Many diseases linked in some way to diet—heart disease, high blood pressure, cancer, diabetes, dental cavities, and others—still plague us.

Americans have also changed their eating patterns over the years. Whereas breakfast used to be the most important meal of the day, today only 53 percent of adults—and only 85 percent of children age five or younger—eat breakfast. In addition, eating out has become more common. One survey found that over half the women questioned ate out on a given day, and 88 percent ate out at least once over a 4-day period. Snacks now provide about 18 percent of the calories in the average U.S. diet.

What foods provide the calories in the U.S. diet? The largest share of calories comes from grain products and from meat, poultry, and fish. Fats, sweets, and beverages combined contribute about as many calories as fruit and vegetables or dairy products. Eggs, beans, nuts, and seeds combined account for the smallest proportion of calories in the U.S. diet.

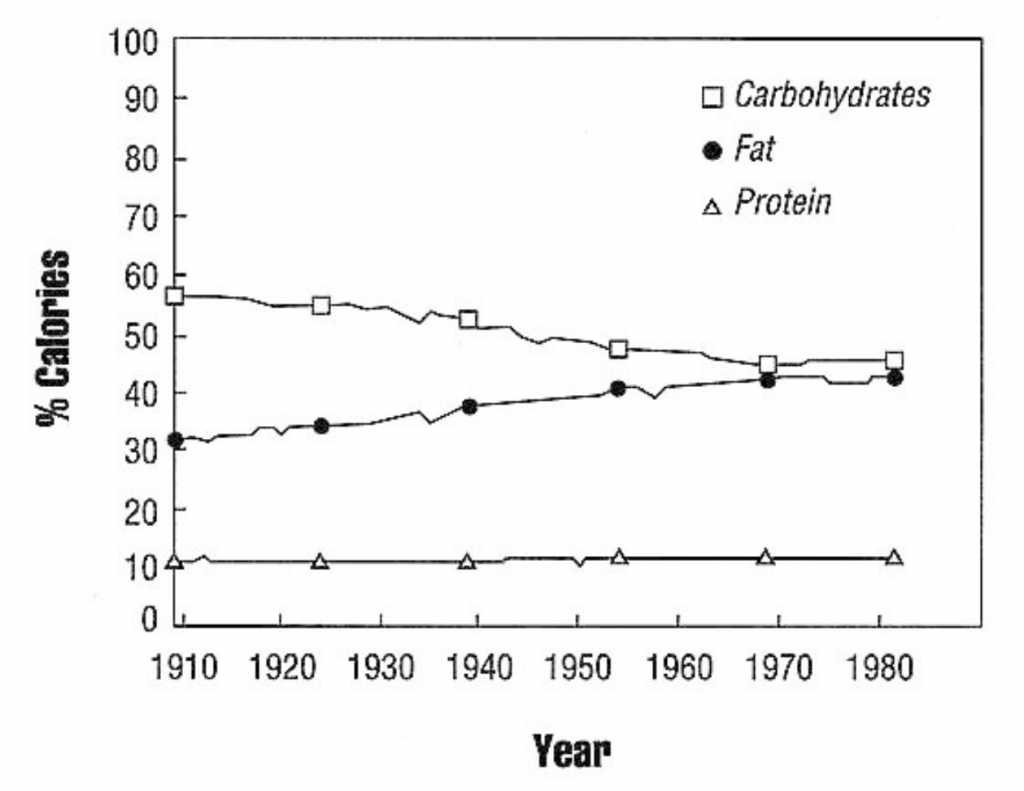

Calories from protein have remained fairly constant during this century, at about 17 percent of total calories.

We also eat proportionately fewer carbohydrates than Americans did at the turn of the century; carbohydrates today account for 43 percent of the calories in the food supply, compared with 57 percent in 1909. In 1909, two-thirds of the carbohydrates in the food supply were complex polysaccharides, and one-third were simple sugars. Today, over half the carbohydrate calories are from sugars, with less than half coming from starches.

The source of the calories in the food supply has changed. Fats now provide about 40 percent of the calories in the U.S. diet, compared with only 32 percent in 1909. The amount of polyunsaturated fatty acids and monounsaturated fatty acids in the U.S. diet increased more than the amount of saturated fatty acids during that period. Americans today eat about 385 mg of cholesterol a day, which is probably less than our grandparents ate because we consume fewer eggs and less butter than they did.

Given the changes that have occurred in the U.S. food supply during this century, it is surprising that Americans today have available about the same level of calories as our grandparents did at the turn of the century. At the same time, we weigh more than our grandparents, suggesting that we do not get as much exercise as was once common.

Today, refrigerated rail cars, trucks, and cargo planes make seasonal foods available year-round. A cornucopia of canned, frozen, fermented, and dried foods appears on grocery store shelves, as do the foods seen nowhere in nature that come out of our country’s food laboratories, such as “fruit” drinks that have no fruit juice and “meats” made from soybeans or wheat gluten. Supermarkets now carry as many as 30,000 different items, making the U.S. diet the most varied in the world.

In the two centuries that have passed since then, the U.S. diet has undergone remarkable changes. In 1800, 95 percent of all Americans ate food that was straight off the farm, or fresh from the sea, with little processing done to it. Today, 95 percent of all Americans depend on others to produce, process, and distribute food to supermarkets. What we can eat depends mostly on what we can afford to buy.

The second important change accompanied the Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth century. The rise of factories gave birth to a new middle class of merchants and managers who had the money to afford a variety of foods. This demand prompted farmers to improve their methods and grow a wider variety of crops. The result was that the amount of food available to all people, both middle class and poor, increased. At the same time, the cost of food dropped significantly.

Two things happened to change the human diet. The first took place around 10,000 B.C., when some people became farmers. For the first time, dairy products and cereal grains became a part of the diet, and the supply of meat became more predictable.

For most of human history, the quest for sufficient food was the chief occupation of the earth’s people. Our early ancestors were hunter-gatherers, searching for edible plants and killing the occasional animal. Archeologists have found evidence suggesting that the early human diet was about 35 percent meat and 65 percent plant food, though little of it was cereal grains. These people ate very little fat—they ate no dairy products and the meat they ate contained only about 4 percent fat—and only low levels of sodium, but their diets were rich in dietary fiber, calcium, and vitamin C.

Maybe we should just get back to the basics of food love…8)

Michael J. Loomis